Tagu-taguan maliwanag ang buwan. Tayo’y maglaro ng tagu-taguan.

Ispel yes, Y-E-S. Ispel no, N-O, and out you go.

Wala sa likod wala sa harap wala sa kanan wala sa kaliwa.

Tagu-taguan maliwanag ang buwan. Tayo’y maglaro ng tagu-taguan. . . .

Game? Game na ba?

GAME!

PANIMULALumaki kaming magpipinsang naglalaro ng taguan. Sa malawak na hardin n gaming lola ditto sa New Manila, sa lilim ng mga mababangong calachuchi at matatayog na mangga, sa liwanag ng maamong buwan at malamig na hangin, natatandaan io kaming nagtatakbuhan at nagtatawanan, inaawit ang awit ng taguan na inawit na ng napakaraming bata kung saan-saan, ngayon at magpakailanman. “Tagu-taguan, maliwanag ang buwan. Tayo’y maglaro ng tagu-taguan. . . .” At natatandaan ko kung paano kami nagtatago sa mga sanga ng calachuchi, o sa likod ng mga malalaking bato. Pinipigil naming ang aming paghinga sa tuwing dadaan ang tayâ. At natatandaan ko rin tuwing ako ang nagiging tayâ, mabilis ang pintig ng puso, hinuhulaan ang pinagtataguan ng bawat isa— dito kaya o doon, sabay bagsak— “Boom-Noel-save!” at sabay takbo, unahan sa base. At uulit na naman ang laro ng taguan.

Ngayong binabalikan ko ang halos dalawang taon kong pagtatampisaw sa tubig ng Pilosopiya, nabubuhay sa aking alaala itong paglalaro ng taguan, sapagka’t nagsisilbi itong isang tumpak na talinhaga sa kung paano ko natutunang tanawin ang Pilosopiya, ang tao, at ang kanyang kalagayan dito sa mundo.

Ang tao ay naglalaro ng taguan, nagtatago at naghahanap. Bilang naghahanap, tayâ siya. Dala ng udyok ng pagkamangha, nakikipagsapalaran siya sa daigdig, tumutuklas at pilit na ibinababad ang kanyang sarili sa kahiwagahan at lalim ng buong sangkameronan. Ang buong Pilosopiya ngayon ay masasabing isang bukod-tanging gawain ng pagtuklas at pag-uunawa sa buong karanasan ng tao dito sa mundo— at kung ano ngang mga hiwaga ang kanyang natuklasan! Ngunit kasabay ng pagtataya at paghahanap, nagtatarin rin siya. Madalas siyang umaatras sa pag-aalinlangan sapaka’t nakikita rin niya ang katotohanan na, kasabay ng hiwagang ito, siya’y isang limitadong nilalang, at ang mundong kanyang ginagalawan ay nag-aanyong masakit at mapaglinlang.

Nasasaktan ang tao, kaya’t nagkukubli siya. Sinasara niya ang kanyang sarili at nabubuhay sa loob ng isang

konsepto, minsan pa nga sa loob mismo ng mga magaganda at matatayog na salita at ideya ng Pilosopiya. Sapat na sa kanyang tumayo sa pampang ng swimingpul ni Padre Ferriols, wala nang pagnanais pang kumilos o lumundag.

Sa dalawang taon ng aming pamimilosopiya, pinagmunihan namin ang napakaraming magagandang sila at katotohanan: pagmamahal, pag-asa, Meron, pakikipagkapwa. Ngunit sa harap ng hapis na ito, isang hapis na tumatagos sa mismong kaluluwa ng bawat tao at tila nakahabi sa misong istruktura ng lahat ng pagmemeron, paano pa nga ba tayo maaaring mamilosopiya, kung ang pilosopiya nga ay sinasabing mismong nagpapalaya? Tila baga, nabibihag tayo sa loob ng kawalan at kadiliman.

Sinasabi ni Marcel, sa kanyang

Balangkas ng Isang Penomenolohiya at Isang Metapisika ng Pag-asa, na:

Kapag lalong hindi nararanasan na ang buhay ay pagkabihag, lalong nawawala ang pagka-angkop ng diwa na makita ang pagsinag ng liwanag na parang natatabingan, mahiwaga, na bago pa magsimula ang anumang pag-aanalisis ay batid na natin na siyang tahanan ng pag-asa.

Ngunit ano ang nais ipahiwatig ng paghahalong ito ng pag-asa at kadiliman? Sa pag-uunawa sa kinalalagyan ng tao bilang isang tentasyon tungo sa dalawang dulo ng kalwalhatian at kawalan, paghahanap at taguan, tila nauudyok tayong magtanong sa kung ano ang halaga ng Pilosopiya sa harap ng hapis ng sangkatauhan at sangkameronan. Sa isang nilalang na napapasaloob sa kadiliman ng hindi-pagka-alam, kinakasama ang malagim na mukha ng hapis at kawalan, tila ang kasagutan sa tanong na ito ang siyang mag-uudyok sa kanyang magpatuloy sa landas ng pagtuklas, o ipikit ang mga mata, isuko ang pagkatao, at magkubli sa tiyak ngunit malamig na moog ng kanyang sarili.

ANG TAONG TAYÂIsang hiwaga sa tao ang kakayahan niyang mag-isip at maka-alam. Isa itong kaalaman na hindi niya agad natatarok, dala marahil ng kapayakan ng katotohanan nito. Ngunit sa panahong namumulatan nga siya, tila isang tahimik na lindol ang nagaganap: para bagang maliit na batang unang binubuksan ang kanyang mga mata sa kahiwagahan ng kanyang kapaligiran. Tumatalab sa kanya, hindi lamang ang kanyang pinagtutuunan ng pansin, kung hindi ang mismong sarili niyang tumutuon at umuunawa. Alam niyang siya’y nakaka-alam.

Itong pagkamulat sa “Ako” ng tao ay sinasabayan din ng isang kamalayang “Nagtataka ako.” Itong pagtatakang ito ang siyang puso ng dinamismo ng kanyang isip na maka-alam sa lahat: sa pagbabalik-tiklop sa kanyang sarili, at sa paglabas niya sa lahat ng pumapaligid sa kanya. Laging tumatalbog sa bawat pader ng hindi-pagka-alam, lagi siyang naghahanap ng sapat na kahulugan na umaayon sa kanyang isipan.

Ngunit ang pagkamanghang ito ay hindi isang pagtuklas sa malayo at kailâ, kung ‘di sa karaniwan na’t araw-araw nang nakikita. Sa mga salita ni Gallagher, hindi ito isang kaguluhan ng isip, o isang kadiliman, kung ‘di isang “pagtatalaban ng malapit at malayo” — ang pagtanaw sa dating daigdig na gamit ang panibagong mga mata at sariwang pag-uunawa. Sa ganitong paraan niya nararanasan na siya’y umiikot sa dilim. Alam niyang nakaka-alam siya, ngunit ang kaalaman niya ay panandalian lamang. Kaya’t patuloy pa rin ang pagtatanong. Pagtuloy pa rin ang paghahanap. Tulad ng bata sa taguan.

Sa ganitong paraan ng paghahanap at pagtataka nakikilala ng tao ang meron: hindi bilang isang babasahin o konsepto, kung ‘di bilang dalisay na karanasan na natatambad sa simpleng akto ng

pagtingin. Isa itong pagbulaga ng meron. Sa kilos ng kanyang isip, mula sa karanasan, natatauhan siya sa isang sinunang apirmasyon ng kanyang kalagayan bilang tao:

merong meron, at nasa meron ako!

Ganito nga ang natutunan namin sa pag-aaral namin ng Pilosopiya ng Tao. Dito, una kaming hinimok na kilalanin ang aming sinaunang kakayahan na umunawa, isang pag-uunawa na tila isang uri rin ng pagtingin. Hinimok kaming kilalanin at danasin ang kailaliman ng meron, isang laging dinamikong pagtatagpo-pagpapakita. Kaya nga marahil isang pambungad sa metapisika ang siyang ginagamit na paraan upang maunawaan itong Pilosopiya ng Tao— sapagka’t minumulat kami sa katotohanan na kami nga’y mga taong umuunawa (

res cogitans) at may kakayahang mamilosopiya, at ang inuunawa at pinagmumunihan namin ay ang mismong meron.

Sa aming patuloy na pagmamasid sa aming kapaligiran, sa pagbababad sa aming sarili sa kailaliman ng meron, nahihinuha namin na kami’y bahagi lamang ng isang higit na malawak na katotohanan. Tulad ng tao na may udyok na lumabas sa sarili at makipagkapwa, may likas na kilos din ang bawat nagmemeron na magpaalam at magpakilala. Sa pag-apaw na ito, nakikilala ang bawat nagmemeron, at mula dito ang lahat-lahat ay bumubuo ng isang kabuoan na laging nakikipagtalastasan, laging nagpapa-alam at nagpapakita. Sa loob ng komunidad ng mga meron gumagalaw ang tao. Napag-iisa ng isang malalim na pakikibahagi sa akto ng meron (

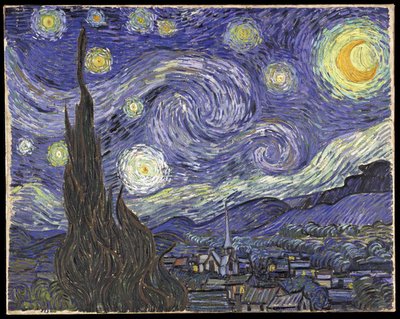

esse), nakakabuo ng isang malalim na kaayusan ang mga nagkaka-iba ngunit nagkakaparehong mga umiiral. Natatambad namin na, kagaya nga ng sinasabi ng mga mistiko at matatanda, siya at ang mga bituwin ay iisa.

Mula rito, makikita ang mismong disenyo ng lahat ng sansinukob bilang isang tumutungo sa kabuoan, kaisahan, at katotohanan. Kagaya ng nakita ni Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, mababatid din na sa lahat ng bagay ay tumutungo sa isang masidhing

personalisasyon na nakakahanap ng kaganapan sa mismong pagmemeron ng tao. Sa ganitong paraan, isang salikop ng pag-iisip ang lahat-lahat: nagsisimula sa pagkamulat sa kanyang isipan, lumalabas ang tao tungo sa lahat ng ibang nagmemeron, ngunit pagkatapos ay bumabalik muli sa kahiwagahan at kahalagahan ng kanyang sarili.

Hindi ito nagtatapos dito, sapagka’t sa pagkilala sa sarili bilang persona, nagigising rin ang tao sa isang katotohanang siya mismo ay tumutungo sa isang higit na persona— ang Mismong Meron na kinakailangang pinagmulan ng lahat, lampas sa lahat, ngunit natatablan pa rin ng isipan. Dito sa

Mismong Meron na ito nahahanap ang prinsipyo ng pagkakaisa na tinutungohan ng buong metapisika, at maging epistemolohiya at etika, at sa Pilosopiya ng Relihiyon ay nakilala namin bilang isang personal na

Absolutong Ikaw. Sa pagkilala sa katangiang maaaring-hindi-magmeron ng lahat-lahat, tila baga tinutulak ang tao ng kanyang kalooban na tanggapin, bilang isang makatwirang katotohanan, ang pag-iral ng isang ubod-tigib-apaw na Meron na nagpa-iral, at patuloy na nagpapa-iral sa lahat.

Mula rito, nakikilala ng tao ang kanyang lugar at tungkulin sa

cosmos bilang nilalang na inuunawaa ang lahat ng nagpapaunawa upang makapagsilbi siyang tagapaggitna sa pagitan ng meron ng panahon at ng Meron na Magpakailanman. Sa kanyang udyok na ilikom ang lahat ng nagmemeron sa kanyang kalooban at alaala, sa kanyang kakayahang pumaloob sa esensya ng bawat isa at ng lahat-lahat, itinataas niya ang lahat ng sanlinikha sa isang uri ng paglampas na siyang nagiging paraan ng pagbalik ng buong sangkameronan sa Kanya na kanilang pinagmulan (

reditus). Kaya nga naman nagkakaroon ng panibago at mas malalim na kahulugan ang mga katagang, “Dumanas ka! Tumingin ka!” sapagka’t sa pagdanas at pagtingin na ito natutupad ng tao ang kanyang tungkulin at tawag na pumagitna sa ngayon at sa magpakailanman.

Sa pagkilala niya sa kanyang sarili bilang tao at sa pagtupad niya sa kanyang tungkulin bilang bahagi ng buong sangkameronan, ipinagdiriwang ngayon ng tao ang kanyang pag-iral. Gumagalaw siya sa galak ng pagtuklas, muli’t-muling dumaranas, umuunawa, at ibinababad ang sarili sa kahiwagahan ng meronng kanyang ginagalawan.

ANG TAONG NAGTATAGOSa pakikipagsapalarang ito, nakikita rin ng tao na, kasabay ng paghahagilap niya sa buong kahiwagahan ng meron, isa isang limitadong nilalang. Kinikilala niya na isa siyang

meron-na-tumutungo-sa-kamatayan. At bagama’t ninanais niyang tumupad sa isang malalim na pagkakaisa sa kanyang kapwa, sa buong sanlinikha, at maging sa mismong Meron, gumagalaw pa rin ang isang halos hindi-maipaliwanag na pagkakahiwalay, sa isang “basag na daigdig” na umiikot sa loob ng isang madilim na hindi-pagka-alam. Sa pagtanaw sa kanyang mismong kasaysayan, nakikita niya ang paulit-ulit na pag-uwi sa pagwawala, at nagtatanong siya kung meron ba talagang halaga ang pagmemeron ng lahat. Nagdududa siya.

Sa kanyang aklat na

Night, inilarawan ni Elie Wiesel ang damdaming ito.

Bukas ang aking mga mata, at nakita kong ako’y nag-iisa— sa isang daigdig na walang Diyos at walang tao. Walang pag-ibig o pagpapatawad. Naging abo na lamang ako. . . .

Nakikilala ngayon ang isang uri ng pakikipagtunggali at gumagalaw sa mismong istruktura ng meron— ang dinamismo na lumampas at tumuklas, sa isang banda, at ang tentasyon na magwala, at manatiling kulob, sa kabila. Kasabay nito ang isang kilos ng hapis na kahirapan sa lahat ng nagmemeron, mula sa pinakamaliit na nilalang hanggang sa kalooban ng tao. Lahat naghihirap, lahat tila naglalaho. Nagtatanong ang tao: maaari nga kayang lumampas, magtiwala, umibig sa harap ng lahat ng hapis na ito na tila nananalatay sa lahat ng nagmemeron? Nalilito ang tao, sapagka’t tila isa itong kababalaghan na hindi kailanman matatablan ng kanyang isipan. Sa kanyang pagtatanong, wala siyang natatanggap na sagot kung ‘di isang malamig na katahimikan.

Kung kaya’t sa kanyang hindi-pagka-alam, sa hapis ng kanyang nararamdaman, lumilikha siya ng ga moog na matibay at matatag. Nagtatago siya. Sa isang paraan, pinapatay niya ang kakayahan niyang umunawa at mag-isip, at nabubuhay sa pagwawala. Dito sa loob ng kaharian ng kadiliman, tinatanong niya kung bakit pa kailangang magpatuloy, kung uuwi lang din lang sa absurdo ang kanyang pag-iral. Nahulog na nga siya sa desperasyon, at sa pakiwari niya’y wala na ang kanya’y sasalo.

Sa taong nagtatago, walang ibang umiiral sa kanya kung ‘di ang kanyang sarili. Pinutol na niya ang kanyang pagbaling sa meron at sa kanyang kapwa. Malinis ang daigdig niya, ngunit hungkag. Gayunpaman, hindi niya nalalaman na ito’y hungkag. Hindi niya nalalaman na sarado ang kanyang sarili.

Ano ngayon ang maaaring makapagbuwag sa mga pader na ito ng pagtatago? Ano ngayon ang maaaring maiharap na sagot sa mismong paghihirap na ito ng sangkameronan, ngayong tila naitulak na ang buong sanlinikha na harapin ang maselang kondisyon ng kanyang pag-iral? Ano kaya ang wastong atitud na kailangang pairalin sa mga nahulog sa loob ng kadilimang ito?

Sa isang paraan, maaaring ituring ang hapis bilang patunay sa pagka-absurdo ng lahat. Sa ganitong atitud, nagiging isang bilangguan ang buhay, isang nausea na hindi maaaring takasan, kagaya ng paningin ni Sartre. Dito, ang tao ay nananatiling naghahanap ng kahulugan, ngunit sa kanyang paghahanap, nakikita niya na ang lahat ay kawalan na hinding-hindi matatablan ng kanyang isipan, o kung hindi man, isusuko niya ang mismong kakayahan niyang lumampas sa kanyang hapis para tanggapin na lamang ang buhay bilang absurdo at walang kahulugan.

Dito, nag-aanyong Sisipo ang tao na pinagninilayan ang kanyang pasaning bato. Sa

pagkamulat sa kanyang absurdong kalagayan, nagkakamit ang tao ng isang

absurdong tagumpay. Kinikilala niya ang kawalang-kahulugan ng kanyang pag-iral, at maging ang pag-iral ng lahat-lahat, at sa panahong ito ng pagkamulat, humihigit siya sa kanyang bato. Ngunit babalik uli siya sa baba ng bundok upang itulak muli paakyat ang bato, upang gumulong muli paibaba, para itulak muli paakyat.

Ngunit sa kabilang panig naman, maaaring tingnan ang paghihirap at hapis na ito bilang isang pagkakataon ng

pagdadalisay o

paghahandog ng sarili. Hindi niya tinatanggap ang pagka-absurdo ng kanyang karanasan; nananalig siya sa nakatago nitong kahulugan. Sa gitna ng kadiliman, hindi niya isinusuko ang kanyang sarili, bagkus, patuloy na umaasa.

Tungkol sa kadilimang ito, sinasabi ni Simone Weil:

Sa loob ng kadiliman, walang maaaring ibigin. Ngunit ang higit na kahindik-hindik ay kung, sa gitna ng kadiliman, mismong pinipili ng taong huwag magmahal, magiging ganap na ang pagkawala ng Diyos. Kailangang patuloy na magmahal ang tao sa loob ng kawalan, o kung hindi ay gustuhin man lamang na magmahal. . . . Pagkatapos, isang araw, darating ang Diyos para ipakita ang kanyang sarili at ibahagi sa taong ito ang mismong kagandahang ng mundo. . . .

Marahil sa pagsasa-walang-laman ng tao lamang siya maaaring mapuno muli. Ang taong tinatanaw ang hapis na may atitud ng paghahanog ng sarili ay naniniwala na hindi maaaring suminag ang katotohanan at kahulugan kung hindi muna dumaraan sa hapis at kawalan, sapagka’t sa hapis “malilikha muli ng tao ang kanyang sarili.” Sa ganitong paraan, yinayakap ng kanyang buong katauhan ang katotohanan ng hapis at kawalan, panatag sa kaalaman na may gumagalaw na kahulugan sa likod nito— hindi lang basta isang absurdong kilos ng meron.

Dahil dito, kumikilos pa rin ang isang uri ng

kalayaan na magpasya at lumampas. Gumagalaw ngayon ang tao sa loob ng dalawang magkabilang dulo ng kahirapan at katiwasayan, ng pagtatago at paghahanap bilang mismong istruktura ng meron. Sa madaling salita, kinikilala ng atitud na ito na hindi maaaring umiral ang tao sa kaligayahan kung wala itong kalakip na hapis at kahirapan.

Sa pagtingin sa hapis bilang pagdadalisay at pagkakataon na ihandog ang sarili, nagsisilbing mismong paraan ng paglampas ito tungo sa isang mas mataas na katotohanan, isang paglundag ula sa isang mababang nibel ng meron patungo sa isang mas mataas na nibel. Upang makalampas, ngayon, kinakailangang harapin ng tao ang mismong hapis ng buong sangkameronan at tingnan ito bilang isang makahulugang karanasan: ang tanging daan ng kaligtasan at kapatawaran, patungo sa kanyang kapwa at sa Absolutong Ikaw.

Sa ganitong paraan, makikita nga na habang nakalugmok sa hapis ang taong nagtatago, gumagalaw pa rin ang kanyang diwa sa loob ng pag-asa. Kinikilala niay ang presensya ng kanyang kapwa-tao na siyang naghahanap sa kanya, at ang Absolutong Ikaw na tumatawag sa kanya. Sa wakas, nag-aanyong isang katwang

biyaya ang mismong hapis, sapagka’t binubuhay nito ang potensyal para matagpuan, mahango mula sa lamig ng kadiliman, at sa wakas, mailigtas.

ANG PILOSOPIYA BILANG LARO NG PAGHAHADOG AT GALAKNgayong kinikilala natin ang ating mga sarili bilang isang nakakagat sa mismong meron, at umiiral sa isang komunidad ng mga umiiral, kinakailangan ngayon ng tao na isabuhay ang kanyang tungkulin bilang tagapaggitna. Sa pagkilala at pag-angkin rin sa nakasangkap na hapis sa buong sangkameronan, higit na napapatingkad ang pagsasagitna na ito bilang isang kilos ng paghahandog ng sarili.

Sa pagtanaw naman ng Pilosopiya sa hapis ng sangkameronan bilang landas ng paglampas at kaligtasan, sa pagkilala sa katotohanan ng pagdurusa ng kapwa, tinatawag nito ngayon ang tao na pumagitna sa hapis na ito, at maging mismong handog para sa kanyang kapwang katulad din niyang naghahapis. Gaya nga ng nasabi ni Manny Dy, “Ang pag-aalay ng aking sarili ay ang pag-aalay ng aking loob, kaisipan, damdamin, at mga karanasan sa kapwa— sa madaling salita, ang buong

buhay ko. Isang pagbabahagi ng sarili ko sa kapwa ang pagmamahal.” Dito natin sa wakas nauunawaan ang paghahandog na ito bilang mismong

kadalisayan ng pagmamahal, na kung saan tunay ngang lumalampas ang tao mula sa kanyang sarili patungo sa kanyang kapwa, mula sa pagkakulob ng sarili patungo sa isang mas matayog at malwalhating pagkaka-isa at pagpapahalaga.

Nasa atin ngayon na tugunan ang tawag ng paghahanap at paghahandog na ito sa ating pakikipagsapalaran sa mundo. Tulad tayo ng mga batang naglalaro ng taguan, isang mahiwagang laro ng pagtatago at paghahanap. Sa paglalarong ito tumutubo ang isang galak ng pagtuklas at paghahandog ng pagmamahal na siyang nasa puso ng karanasan at gawa ng Pilosopiya.

“Boom-TAO-save!” sabay takbo, pabalik sa base. At uulit na naman ang laro ng taguan.

Why love, if losing hurts so much? I have no answers anymore,

only the life I’ve lived. Twice in that life I’ve been given

the choice, as a boy and as a man.

The boy chose safety. The man chooses suffering.

The pain, now, is part of the happiness, then. That’s the deal.

from A Death Observed, by C.S. Lewis

Perhaps in our hour of brokenness of body or anguish of spirit,

we have even touched the wood of his cross,

and known something of the presence of that love

which hangs there, which is the love of God Hiself—

greater than the sum of our fears and the evil in the world.

from And They Shall Name Him Emmanuel

by Fr. Catalino G. Arévalo

Early this morning, the President of the Republic, over a live televised address to the nation, declared a State of Emergency, invoking her powers as Commander-in-Chief, thereby calling out all the armed forces “to suppress lawless violence, invasion and rebellion,” as clearly set forth in the Constitution.

Early this morning, the President of the Republic, over a live televised address to the nation, declared a State of Emergency, invoking her powers as Commander-in-Chief, thereby calling out all the armed forces “to suppress lawless violence, invasion and rebellion,” as clearly set forth in the Constitution. I will not, at this point, add my personal commentary or opinion on the actions taken by the President today. I think more qualified and credible legal minds will take care of this as the days progress. I will, however, share some insights which came to me as I was watching the evening news, listening to statements of police officers warning unruly demonstrators that those who chose to defy the military dispersals would be arrested without warrant and detained indefinitely without charge. The statement, of course, is not only misleading, but carelessly and incorrectly made. To this, a friend and colleague of mine earlier commented how many of our citizens simply are not aware of their Constitutionally protected rights. To this, I replied: not only are they unaware, but I suspect, they are also very unappreciative, or even apathetic.

I will not, at this point, add my personal commentary or opinion on the actions taken by the President today. I think more qualified and credible legal minds will take care of this as the days progress. I will, however, share some insights which came to me as I was watching the evening news, listening to statements of police officers warning unruly demonstrators that those who chose to defy the military dispersals would be arrested without warrant and detained indefinitely without charge. The statement, of course, is not only misleading, but carelessly and incorrectly made. To this, a friend and colleague of mine earlier commented how many of our citizens simply are not aware of their Constitutionally protected rights. To this, I replied: not only are they unaware, but I suspect, they are also very unappreciative, or even apathetic.